175 years of History

In 1840, William Foster Nye, barely 16 years old, left his family’s Cape Cod farm to carve his niche in the world of commerce. Before his death 70 years later, he would create a line of lubricating oils sought around the globe – and a company that still bears his name today.

In 1840, William Foster Nye, barely 16 years old, left his family’s Cape Cod farm to carve his niche in the world of commerce. Before his death 70 years later, he would create a line of lubricating oils sought around the globe – and a company that still bears his name today.

Apprentice to a master carpenter, Nye began his long career in New Bedford, Massachusetts. But he had a wanderlust to quench before settling into what would eventually become a lifelong pursuit.

He left New Bedford to build organs in Boston, took to sea as a ship’s carpenter, worked at an ice house in Calcutta and went to California for the Gold Rush, where he built a profitable business as a stair builder after the San Francisco fire. He returned to New Bedford to start an oil and kerosene business, and then left to serve in the Union Army as a sutler, a traveling merchant – the first to set up shop in Richmond after the defeat of the Confederate Army.

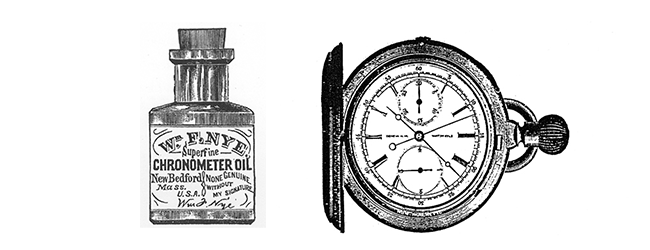

In 1865, he returned again to New Bedford and the oil business, first out of the kitchen of his Fairhaven home, then from a small store front in New Bedford. He sold a wide assortment of oils: burning oils, lubricating oils, even castor oil and salad oil. But the market niche he set out to capture was lubricating oils for delicate machinery: watches, clocks, chronometers, and later, sewing machines, typewriters, bicycles and electrical instruments.

In 1865, he returned again to New Bedford and the oil business, first out of the kitchen of his Fairhaven home, then from a small store front in New Bedford. He sold a wide assortment of oils: burning oils, lubricating oils, even castor oil and salad oil. But the market niche he set out to capture was lubricating oils for delicate machinery: watches, clocks, chronometers, and later, sewing machines, typewriters, bicycles and electrical instruments.

He capitalized on the work of New Bedford watch maker Ezra Kelley. Kelley discovered that oil from the jaw and head of the porpoise and blackfish proved superior to any other known lubricant for delicate mechanisms, and his oil, which he began selling in 1844, had become a benchmark industry. Nye became Kelley’s chief competitor. He developed his own brand of “fish jaw oil,” but had to overcome strong market resistance to a new brand name. He started at the top. With the help of a trade journal publisher, he persuaded Cross and Beguelin, a leading manufacturer of watch and clock components in New York, to try his new formulation. Impressed with its quality, they adopted it as their own, and word about Nye’s oil quickly spread throughout the industry.

Within 10 years, Nye had moved from his small, rented storefront to his own stone factory on Fish Island in New Bedford – and he was well on his way to building a solid reputation for having “the best watch oil in the world.”

Nye’s rise to fame as a world-class manufacturer of specialty oils was propelled by a marketing effort that would be the envy of any modern-day entrepreneur.

Nye frequently exhibited his product at the “trade shows” of the day – including several World Fairs, the Columbian Exposition, the Paris Expo of 1889, where Gustav Eiffel unveiled his famous tower. At industry symposia, he presented papers on his oils that, according to the press, “were used by inventors of electrical appliances, locomotive speed recorders…and the most delicate automatic machinery.”

By 1889, William F. Nye, the consummate marketer, had become the largest manufacturer of sewing machine, watch and clock oils in the world, producing more than 150 thousand gallons annually for bulk delivery – plus over two million bottles for jobbers and retail sales. In January of 1896, he absorbed his chief competitor, Kelley, and established an unbroken line to the 1844 origin of this specialized business. By year’s end he had tripled the size of his factory, cornered the market on raw materials, stockpiled nine-tenths of all fish jaw oil in the world – and captured the world market.

Jan. 12th, 1896

Jan. 12th, 1896

Dear Mr. Nye,

I have been in the watch repairing business for the past four years, and have used your oil on every watch I have cleaned, which has been about 3,000, and have never had a customer say his watch stopped from freezing weather. I enclose you a weather report of this place, so you can see for yourself 50° below zero, which is very cold, and it has been lower still.A. L. H. Brown, Watchmaker

Calgary, Alberta, N.W. Ter., Canada

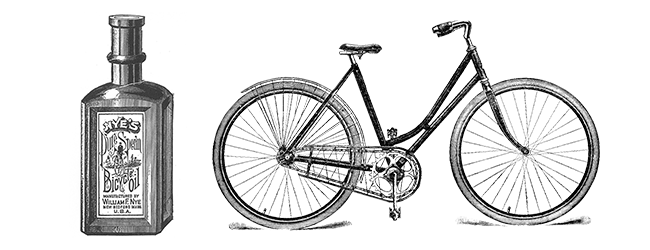

Nye had an uncanny ability to identify a profitable market niche. One example: the bicycle – a U.S. industry that went from zero to $60 million in sales in less than seven years.

Shortly after bicycle’s introduction to the U.S. in 1889, Nye introduced “Lily White,” a pure white, stainless, bicycle oil. He exhibited it to rave reviews at the first national bicycle show in Madison Square Garden in 1897, where he offered a reward of “$1,000 to anyone producing an oil equal in every essential quality to his own.”

No one accepted the challenge... NICHE CAPTURED.

Nye believed in marketing, but quality products, each responding to a particular market need, were the foundation of his company’s success. In 1901, as reported in his home town newspaper, he attended the Pan American Exhibit with no less than 32 varieties of oils, “each adapted to their specific applications as to their fire test, cold test, specific gravity and viscosity.

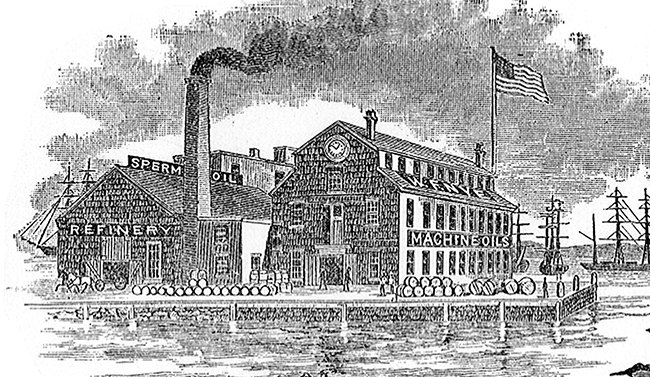

Fish Island: The Nye oil refinery occupied this former three-story landmark on Fish Island in New Bedford Harbor until 1929, when operations were moved to a new facility in Fairhaven. The 1877 stone structure was destroyed in the Hurricane of 1938.

An innovator in the industry, Nye maintained a laboratory at his Fish Island plant in New Bedford Harbor for what today would be called Quality Control and R&D. He also constructed his own bottling machine, patented by his son Joseph, which filled either one, two or three ounce bottles – a gross at a time. Untouched by human hands, the oil passed from tanks on the third floor through pipes directly into the machine, which could fill nearly 4,400 bottles an hour. Spillage from broken bottles was caught in a tray and pumped automatically up three stories to the holding tank.One of the most adventurous quality efforts initiated by Nye was a refinery he established in an old rolling mill in St. Albans, Vermont. To respond to a market demand for an oil that would function at lower temperatures, Nye tried refining his fish jaw oil in the sub-zero, winter temperatures of the Canadian border town. His experiments were successful. The process not only freed the oil from impurities “that corrode or blacken pinions,” but his “St. Albans oil” maintained its lubricating properties from -50° F. to +200° F.

Nye oil became synonymous with quality. It won awards at nearly every exhibition. But perhaps the greatest testimony to its superiority, it was known and asked for by name throughout North and South America, Europe, the Far East, Australia and New Zealand.

Total Quality Management may be a late 20th century concept, but William F. Nye embraced it one hundred years ago.

He directed his son Joseph to establish a porpoise fishery on Cape Hatteras. Several 15 man crews, with boats and seines, would herd porpoise to shore, render the oil from the head and the jaw, and begin the refining process at beach front factories, before shipping the crude oil to Nye’s New Bedford or Vermont refinery.

The result, boasted Nye, was “a much finer article than has been put out by any manufacturer.”

Nye’s porpoise jaw oil sold on the world market until the 1970s, though finding reliable sources for the raw material became progressively more difficult after his death in 1910.

Nye’s son, Joseph, managed the company until 1923 when it passed to business associate and friend Anderson Kelley. The Kelley family operated the firm until 1956, during which time they secured the crude oil from Canada – and from occasional strandings of blackfish on Cape Cod.

The third and current owners, who originally bought the business only for the real estate, decided to rejuvenate the company after seeing its rather impressive client list, which included Bulova Watch, Eastman Kodak, GE and IBM. They continued to obtain raw blackfish head oil from Newfoundland. Later, they formed new supply agreements with a fishing cooperative in the British West Indies, where natives still hunted blackfish for food.

They also saw the handwriting on the wall; the harvesting of ocean mammals was threatening their extinction. In the early 1960’s, more than a decade before the Marine Mammal Protection Act outlawed the importing of the company’s traditional raw material, the new owners began the transition from porpoise oil and petroleum-based products to synthetic functional fluids.

Today, synthetic hydrocarbons, esters, polyglycols, silicones, polyphenyl, and fluorinated ethers are the “raw materials” for Nye lubricants. But, the tradition that began more than 150 years ago continues. For specialty lubricants that meet the most rigorous demands of today’s “delicate machinery,” companies who want the best still turn to Nye.

We’ve changed over the years. Our lubricants, now synthetic, offer far more functionality than petroleum and a porpoise jaw oil ever could. Our application list, though it still includes watches, consists of devices not yet dreamed of in 1844: automotive instrumentation, antilock braking systems, medical and optical instruments, aerospace controls, computer peripherals, and appliance timers, to name a few.

And now with our acquisition by FUCHS Lubricants Company and joining the global FUCHS Group, our resources and global access to markets have taken a leap ahead.

But while our products and applications have changed, the principles upon which this company was founded haven’t changed that much in 175 years. Like William F. Nye, we specialize in lubricants for "delicate machinery." We develop products to meet our customers’ special needs. Most importantly, like our founder, we still stake our reputation on the quality of our products. Then and now, if it bears the name Nye, people expect nothing less.